Previous Issues

Winter 2024. 1540

Autumn 2024. 1539

Summer 2024. 1539

Winter 2023. 1537

Autumn 2023. 1536

Summer 2023. 1535.

Spring 2023. 1534.

Winter 2022. 1533.

Autumn 2022. 1532.

Summer 2022. 531.

Following the dispicable and illegal invasion of Ukraine, the Summer 2022 edition of Musical Opinion carries a large article about Sergei Prokofiev, arguably its most famous composer along with an overview of the Ukrainian classical music scene over the last one...

Spring 2022. 1530.

Winter 2021. 1529.

Autumn 2021. 1528.

Summer 2021. 1527.

Spring 2021. 1526.

Winter 2020. 1525.

Autumn 2020. 1524.

Summer 2020. 1523.

Spring 2020. 1522.

Explore By Topic

Spring 2024. 1538

In Praise of Paul Hindemith, 1895-1963, on the 60th-anniversary of his death

Robert Matthew-Walker

From time to time the subject of fashion in music arises: how it is that the music of one composer, or even what might be termed a ‘school’ of composers, which is widely played and appreciated, tends to leave the concert, recording, or broadcast schedules and enters a period of neglect, perhaps rarely – or never – to return?

Lord Kenneth Clark’s observation, stated at the beginning of his masterly study of Leonardo da Vinci, that “Great art needs to be reinterpreted for each generation”, may be a starting point, but “each generation” – especially in today’s society – cannot have a catch-all identity of its own, the more so as people are demonstrably living longer, resulting in inter-generational differences, that education appears to be in a constant state of flux (not just what is taught – or not taught – but how knowledge is conveyed), and communication in the modern world appears to be obsessed with what Marshall McLuhan (exactly 60 years ago) identified as the concept of “the medium is the message”.

We can become so obsessed with the materials which constitute the ‘medium’ that any ‘message’ becomes very much a secondary matter: as Schoenberg (to slightly misquote him) said: “A Chinese philosopher speaks Chinese – the question is, ‘what is he saying?’.”

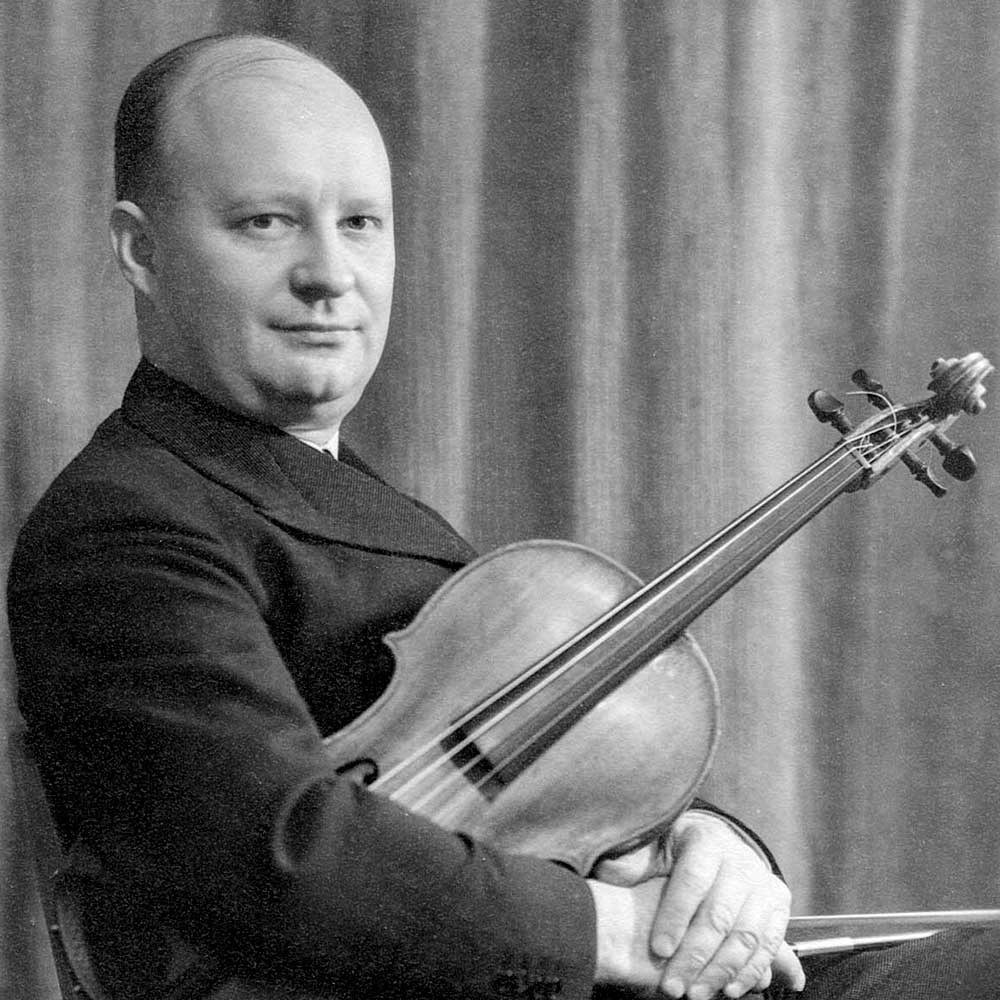

Nikolay Medtner in England

Alexander Karpeyev

Relatively few British concert-goers are familiar with Medtner and his music nowadays, yet in pre-revolutionary Russia he was considered to be the equal of Scriabin and Rachmaninov. Still fewer will be aware that Medtner spent the last 16 years of his life in England. Because his grandparents had emigrated to Russia from Schleswig-Holstein, Germany seemed the obvious refuge when he and his beloved wife Anna escaped Bolshevism in 1921.

Sadly, Medtner found himself categorised as one of many composers still composing in the old-fashioned late-Romantic style. The couple soon moved on to France hoping for a warmer reception only to languish unnoticed and impoverished for nearly a decade. By 1933 Medtner had resigned himself to returning to the USSR but was refused a visa. Further to his dismay, his music was banned and would remain so until Stalin’s death in 1953. The only highlight of those years was the brief visit to England in 1928 when he was made an Honorary Member of the Royal Academy of Music. Rachmaninoff telegraphed him with congratulations: ‘I am happy to state that a new country has appeared that has appreciated you’. That recognition, together with a timely offer of accommodation from a family friend, inspired the Medtners to relocate again. Before leaving France, Medtner embraced Russian Orthodoxy, having previously been Lutheran and chose Sergey Rachmaninoff as his godfather. The choice reflected the degree of their closeness in immigration.

Towards the Rhapsody in Blue

Lawrence James

Marking the Centenary of the first performance of this iconic work, the Editor outlines the background which led to its composition

In 1919, when only 20 years old, George Gershwin wrote the song that was his initial breakthrough. During that year, he had been commissioned to write the entire score for his first Broadway musical, La, La Lucille, by its aspiring producer, Alex A. Arons. George composed twelve songs, not all of them specifically composed for the show, for some came from a sheaf of earlier numbers. All things considered, the show – which opened at the Henry Miller Theater in New York City on May 26, 1919 – was a success, without it being a particularly notable one; a few of George’s numbers have notable merit, especially ‘Nobody But You’.

This was an excellent beginning for Gershwin on Broadway, and before the year was out he experienced the beginnings of a more important success by way of a show, Capitol Revue, which marked the opening of a New York motion-picture house, the Capitol Theater, on October 24.

Franz Schubert’s Real ‘Unfinished Symphony’

Dr Martin Pulbrook

Contrary to general misconception, Schubert’s final symphony, the Tenth, is missing its fourth and final movement.

In an article ‘Finished but Rejected’ (on Schubert’s Eighth Symphony) in issue 1534 of Musical Opinion (January-March 2023, pp 10-12) I suggested that Schubert’s Eighth was not properly ‘Unfinished’, since its composer completed it but then had doubts about the last two movements and held them back.

The real ‘Unfinished Symphony’ of Schubert’s was the Tenth, being worked on by the composer at the time of his death in November 1828. And the surviving sketches of this, three movements in all, were carefully and most sympathetically edited by Brian Newbould in his ground-breaking 1979-81 edition. We owe Newbould a huge debt of gratitude for what he has done here, for he has given us back the torso of a lost masterpiece. And this article has as its purpose the outlining of a true perspective of what the Tenth Symphony aimed to achieve; for, so far, that purpose and perspective have been sadly and regrettably misunderstood.