Previous Issues

Autumn 2024. 1539

Summer 2024. 1539

Spring 2024. 1538

Winter 2023. 1537

Autumn 2023. 1536

Summer 2023. 1535.

Spring 2023. 1534.

Winter 2022. 1533.

Autumn 2022. 1532.

Summer 2022. 531.

Following the dispicable and illegal invasion of Ukraine, the Summer 2022 edition of Musical Opinion carries a large article about Sergei Prokofiev, arguably its most famous composer along with an overview of the Ukrainian classical music scene over the last one...

Spring 2022. 1530.

Winter 2021. 1529.

Autumn 2021. 1528.

Summer 2021. 1527.

Spring 2021. 1526.

Winter 2020. 1525.

Autumn 2020. 1524.

Summer 2020. 1523.

Spring 2020. 1522.

Explore By Topic

Spring 2025. Issue 1541

Elgar – The March King

Tom Higgins

From music to accompany parading troops, Elgar raised the regimental quick march to concert hall status. Tom Higgins explains the background.

In the year of his 40th birthday, Elgar composed his Imperial March, commemorating Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. It established itself immediately as a great popular success and made Elgar’s name widely known to London audiences. The work expressed perfectly the mood of its time, receiving many contemporary performances, commencing with its premiere in 1897 at the Crystal Palace, conducted by August Manns, of whom more later.

At this point a firm line needs to be drawn between Imperial March, a piece for orchestra offering a quiet, confident view of empire, and a military band quick march designed to accompany parading troops. Extended in construction, Elgar’s work belongs in the concert hall. On the other hand, the more straightforward quick or regimental march seldom ventured outside of its intended environment. Photo Freepik

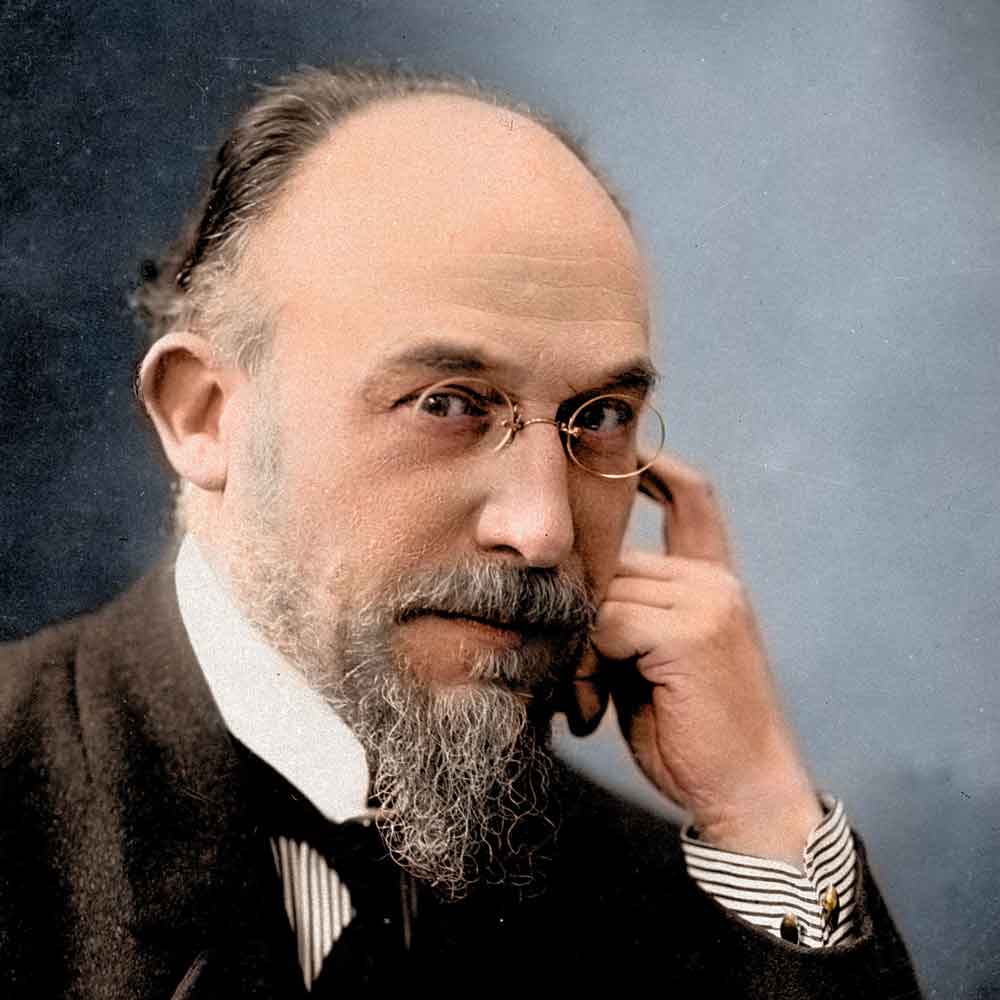

Still an enigma? More reflections and questions on Satie’s Vexations.

Richard Leigh Harris

For the past century and a quarter, the various unanswered questions arising from Satie’s puzzling piece Vexations continues to both intrigue and frustrate performers and Satie scholars alike.

It is, perhaps, an irony that Satie himself might have relished with quiet delight, guffawing into his hand and beard: namely, that various issues surrounding the performance of Vexations continue to vex and irritate; an itch that cannot be adequately scratched and that will not be readily appeased.

Early Satie writers and scholars invariably failed to mention Vexations at all, probably assuming that it was one of Satie’s droll (and less funny) jokes. Neither Templier (1932) or Myers (1948) mention it in passing or even as footnotes, whilst Harding (1975) dismisses it as a mere frippery.

Vexations was written in the first half of 1893, probably in April at around the same time as his minature Easter gift to his lover Suzanne Valadon, Bonjour Biqui, Bonjour! (This fragment, in common with Vexations, is marked Tres lent and consists of three diminished chords only). It could almost be seen and heard to act as an ‘upbeat’ or in-breath to Vexations. Photo Wikimedia

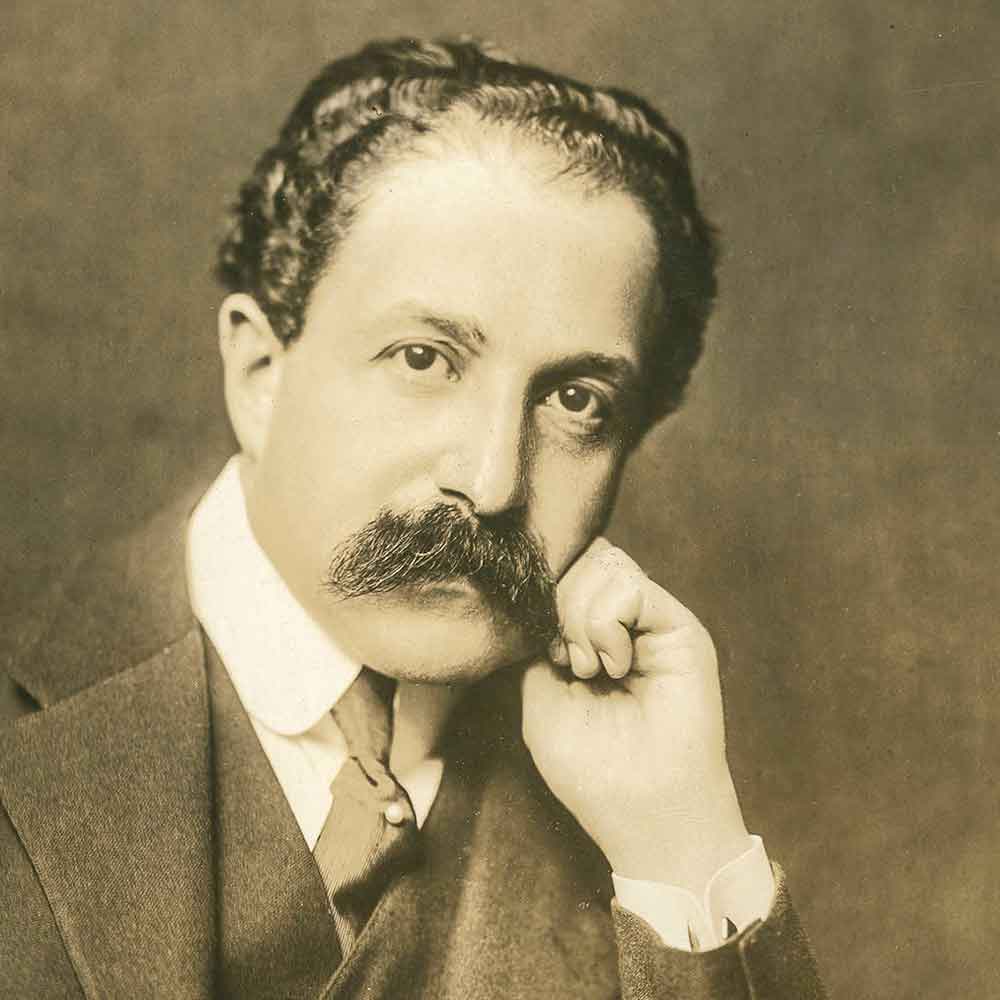

Pierre Monteux (1875-1964) - Aspects of a Great Conductor a Sesquicentenary Tribute

Robert Matthew-Walker

Pierre Monteux, arguably the greatest French conductor of the twentieth-century, was born in Paris in April 1875 and died in the town of Hancock, in the state of Maine, USA, in 1964. His death occurred a few weeks before he was due to make his debut at the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts in London at the age of 89, in a week of programmes alternating nightly at the Royal Albert Hall with Leopold Stokowski, then a mere 82 years old. At the time of his death, Monteux was principal conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra, having been appointed to the post at the age of 86: his contract with the LSO stipulated that he serve a 25-year engagement.

On May 29th, 1963, Monteux had conducted the London Symphony Orchestra at the Royal Albert Hall in a concert marking the 50th anniversary of the first performance of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (Le Sacre du Printemps) – Monteux had conducted that first performance in Paris in 1913 when he was music director of Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. The Royal Albert Hall programme began with Wagner’s Prelude to Die Meistersinger, followed by Brahms’s Second Piano Concerto with the American pianist Van Cliburn (the first prize-winner of the inaugural Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1958) as soloist. The Rite of Spring was the single work in the second half. Photo Wikimedia.

The Adventures of Sam

Monica McCabe

Fifty years ago (or half a century, which makes it sound even longer) Granada TV began to broadcast a television series called Sam. This was a family drama, based around the story of a boy growing up in the deprived north of England, in an imaginary coal-mining town named Skellerton. The drama eventually ran to 39 episodes, and was an immense popular success. The theme tune for the series was written by my late husband, John McCabe, and he eschewed the hackneyed go-to idea of a brass band, which runs in the heads of all television producers of northern-based programmes. Instead he used a small instrumental group with percussion, and a solo trumpet for the introductory tune. The theme became a huge hit, and was chosen in a TV Times viewer poll as one of the Top Twelve TV Themes of the Year, along with such gems as the themes from Hawaii 5-0, The Onedin Line (Spartacus of course) and Colditz, among others. The 12 voted-for themes were even played at the Royal Albert Hall, and recorded by Jack Parnell and his Orchestra, John’s supposedly in an ‘arrangement’, which John always claimed consisted of their taking one instrument out – thus entitling Parnell to an arranger’s fee, and a substantial cut of the royalties.

Granada TV, under Lord (Sidney) Bernstein, and Managing Director Sir Denis Forman, was at the peak of its magnificent form at that time, with such splendid offerings as Brideshead Revisited, and The Jewel in The Crown, rivalling the BBC then, and probably beating it hands down today. Photo Gareth Arnold

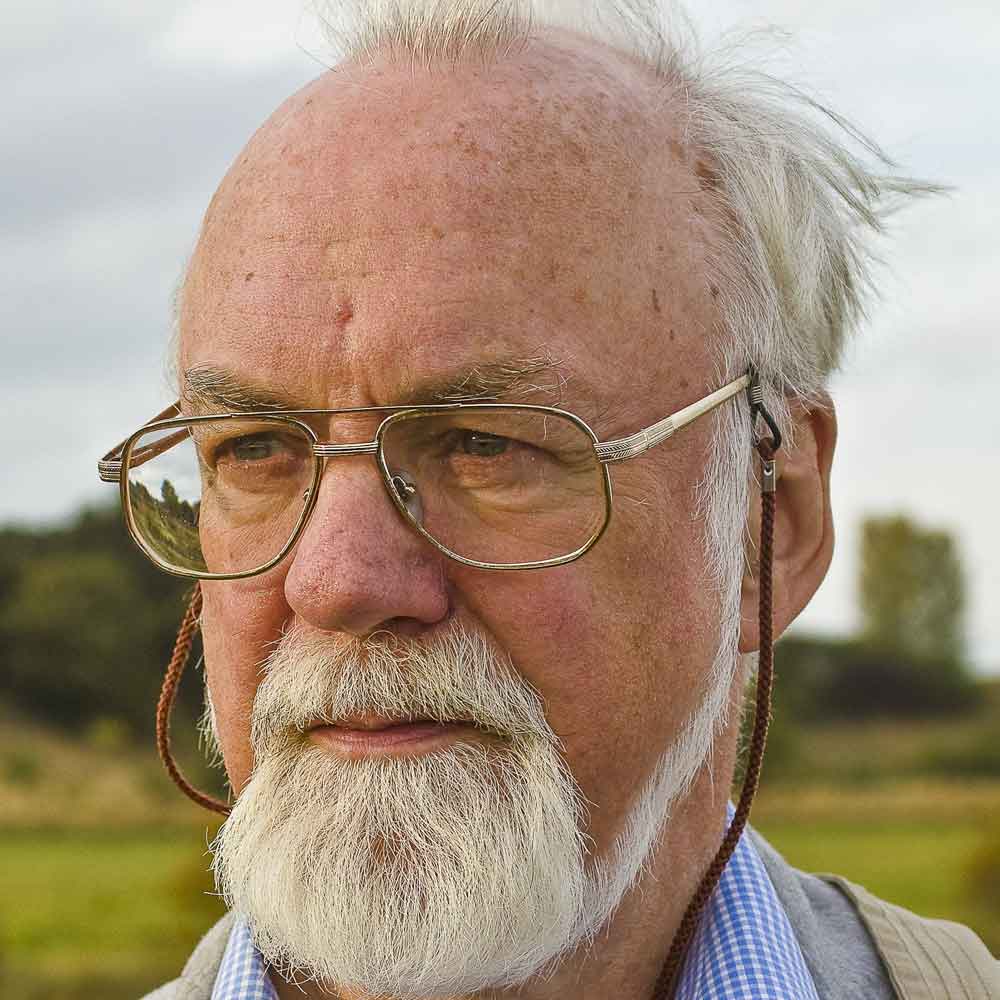

MT and Me

Edward Clark

MT refers to Sir Michael Tippett. Me refers to the author, above, who has enjoyed a life-time’s admiration for the extraordinary contribution MT has left to British music.

In my opinion his legacy is the greatest of all English composers since Elgar. There have been other giants but none greater than MT.

I first heard MT’s music at school. It was the captivating Concerto for Double String Orchestra conducted by Rudolf Barshai, an LP I still enjoy. A later reissue on the MFP label was conducted by Walter Goehr, one of MT’s earliest advocates, who conducted the premiere of A Child of Our Time.

Since then I have followed MT’s career at first hand. The range of his world in music is enormous, not always immediately understood but of sufficient value deserving of my perseverance. I attended the premiere of The Knot Garden in 1969, a shock to me and many others. It came soon after the premiere of The Vision of Saint Augustine (1965), a truly powerful work that I heard subsequently at The Proms. These two works entered my inner life, baffling but worth staying with. Photo: originally www.tippettfoundation.org.uk/biography

Clive Osgood – a composer of today

Oliver Condy

After a brief but majestic, Haydn-esque introduction, Clive Osgood’s Magnificat bursts from the blocks in a Bachian blaze of glory. Choral lines weave in and around each other amid flurries of orchestral strings and radiant brass, infused with infectious Latin rhythms that sweep the music along with infectious, sparkling energy. This is music that nods to tradition, but which is unmistakeably new. As Osgood says, he’s taken inspiration from the 18th century, and given it “a 20th-century glaze.”

“My favourite composers are 18th century: Mozart, Bach,” says Osgood. “I recently wrote a Dixit Dominus modelled on the tonal scheme of the Vivaldi Dixit Dominus – I find that that there’s a vibrant freshness to Vivaldi where every note counts.”

As much as Osgood is influenced by the great Baroque and Classical composers, there’s a rich seam of post-war Englishness running through the Magnificat, too. Photo Mike Cooter