Previous Issues

Winter 2024. 1540

Autumn 2024. 1539

Summer 2024. 1539

Spring 2024. 1538

Winter 2023. 1537

Summer 2023. 1535.

Spring 2023. 1534.

Winter 2022. 1533.

Autumn 2022. 1532.

Summer 2022. 531.

Following the dispicable and illegal invasion of Ukraine, the Summer 2022 edition of Musical Opinion carries a large article about Sergei Prokofiev, arguably its most famous composer along with an overview of the Ukrainian classical music scene over the last one...

Spring 2022. 1530.

Winter 2021. 1529.

Autumn 2021. 1528.

Summer 2021. 1527.

Spring 2021. 1526.

Winter 2020. 1525.

Autumn 2020. 1524.

Summer 2020. 1523.

Spring 2020. 1522.

Explore By Topic

Autumn 2023. 1536

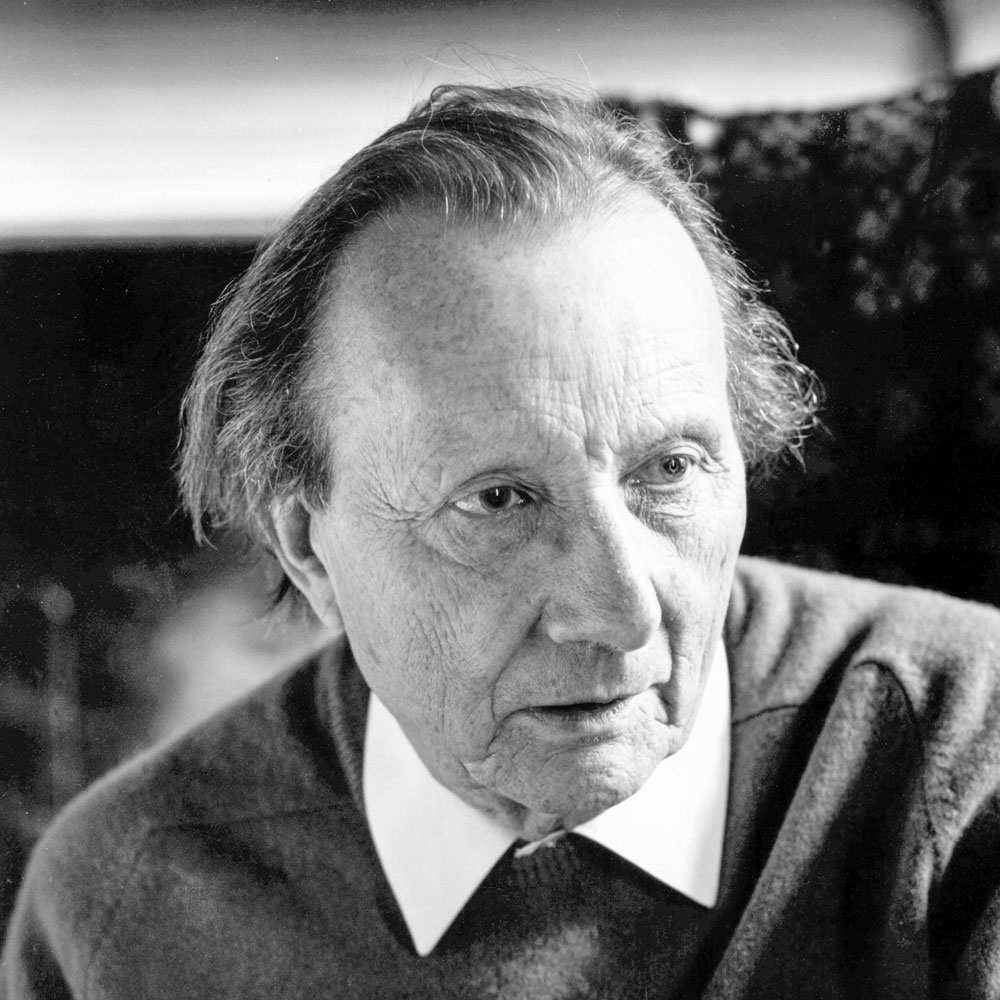

The Legacy of Lennox Berkeley

Peter Dickinson

I first came across Berkeley’s music when I was at school – over seventy years ago. Since then I have given his music the test of time. In the 1950s Berkeley was at the height of his fame and in 1963 I claimed that he was one of the four leading British composers. In order of birth – Walton, Berkeley, Tippett and Britten. I wrote many articles in musical journals about his work, gave BBC talks, and my book The Music of Lennox Berkeley was published in 1988 by Thames Publishing, an independent press run by the late John Bishop who supported many initiatives in British music. I was just able to put the book into the composer’s hands before his Alzheimers overwhelmed him and I think he knew what it was.

The book was aimed at the musical profession, assuming that the general reader could skip the technical passages. It seemed important to make the case for Berkeley at a professional level at that time and the book was well received. However, I now think I was too inclined to take his own valuation of himself as invariably inferior to Britten. He admired Britten enormously but, as several of my interview subjects explained, he was always his own man. I was able to cover some errors and add material in the second edition of the book published by Boydell in 2003, the centenary year, and I hope that everybody will use that edition, sending the earlier one to the charity shops.

John Carewe at 90

A Tribute by Edward Clark

John Carewe is one of the most versatile and well-travelled British conductors in modern times.

He celebrated his 90th birthday earlier this year and is blessed with a demeanour some 30 years younger. His career covers an early enthusiasm for modern music leading to the appointment of Music Director of the BBC Welsh Orchestra (today the National Orchestra of Wales)). There followed a decade conducting many orchestras in South America which led to another decade and more of being conductor of choice for the principal German Radio Symphony Orchestras. At this time he was also frequently invited to conduct various Scandinavian orchestras. He now lives in London, and among the many recordings made over many years two recent ones contain works by David Matthews, Dvořák, Glazunov and Sibelius.

I am hard put to think of a conducting career of such wide-ranging repertoire performed by so many orchestras (and the occasional opera house) at home and abroad and over so many decades.

Vaughan Williams Proffers a Test for Nationalists, the composer's first visit to the US

An Interview by Oscar Thompson, music critic of Musical America, published on June 17, 1922

Clue to art Expression found in the kind of music the uneducated man would write : Not Race Consciousness, but Awakening to Beauties of British Folk Music Chief Factor in Remarkable Development of New English school : Sees element of danger in technical virtuosity : How Reversion to Medieval Music has Freed Melodic Line.

There is nothing of the showman about Ralph Vaughan Williams. Tall, ruddy, heavy-set, his British origin is written in his features and is sounded in his voice. At first sight, he resembles Albert Coates, similarly tall, ruddy, heavy-set and essentially British, for all the Russian admixture of his blood. But Vaughan Williams is not of the genus conductor. The composer of the ‘London’, ‘Sea’ and ‘Pastoral’ Symphonies, though he, too, is no stranger to the baton, has the composer-personality, rather than that of a virtuoso leader of orchestral hosts.

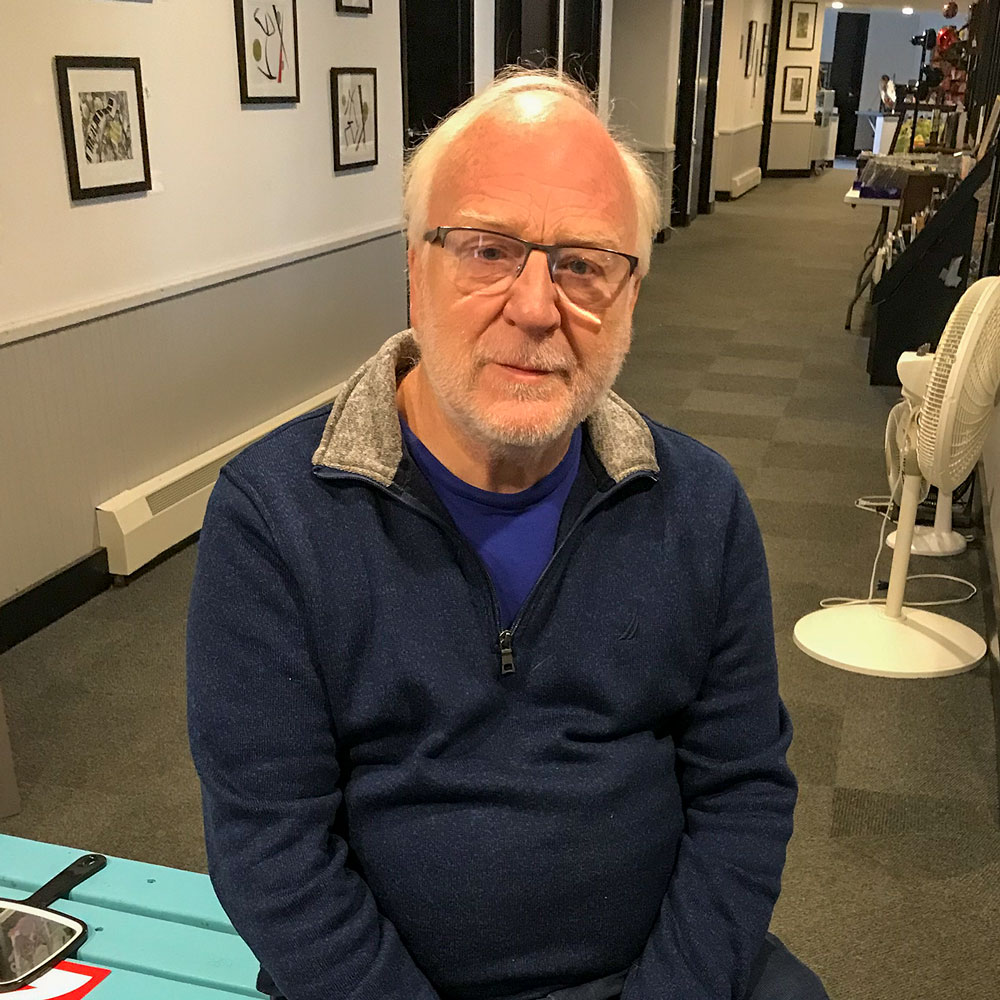

30 Years of Classical Adventure

Stephen Sutton, founder of Divine Art

In 1992, I lived in a very small village in Northumberland, England, by the name of Simonburn. I worked as a commercial lawyer, and also had many connections with the famous 13th century village church of St. Mungo, situated next to our home. As part of the exercise to raise funds for the restoration of our fine Walker organ, I agreed to produce a recording. That was Divine Art’s first release, on cassette only – now on CD of course. It came to the attention of music critics, and led to my meeting several musicians who enlisted my help in producing CDs; they in turn introduced me to colleagues, and though I never intended to become a record producer one thing led to another until now we have an international business, which has acquired a reputation for quality and for introducing new music and fascinating rarities. The company was first based in South Shields, where I carried on my law practice, but we relocated to our new home in East Harlsey, on the edge of the beautiful Hambleton Hills in North Yorkshire, before jumping ship and moving our home and the main office to New England in 2009.

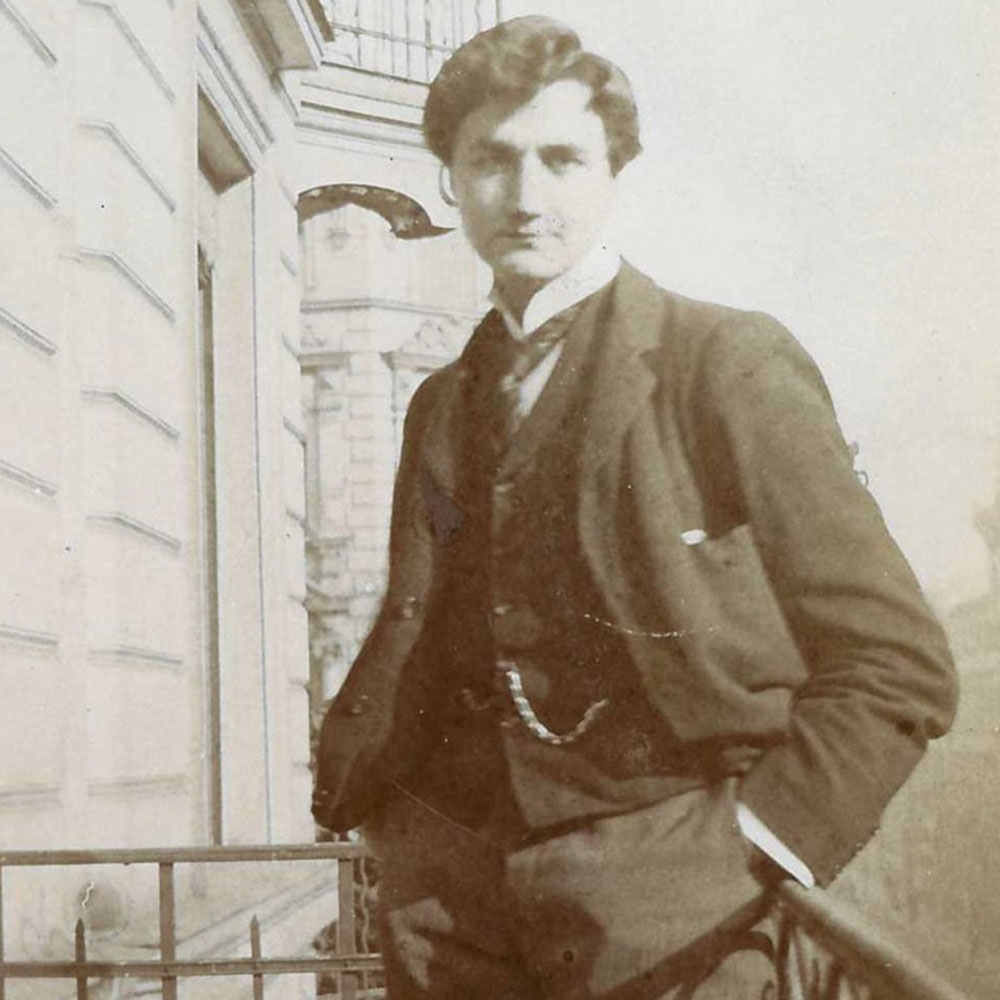

A Conversation with Rachmaninoff

Basil Maine - an interview from 1936

Rachmaninoff began by making a safe assumption. ‘I am a pessimist,’ he said. ‘You know that.’ I had heard as much, of course; and I knew that on the concert platform his look was always that of a world weary man. But I suspected that this was part of the façade that every public artist must devise for self-protection.

‘Well, the last time he was in England, this pessimist had a revelation,’ he continued. The world-weary look gave way to a mask-like smile. He spoke slowly in a deep, remote-sounding voice, as if he were not so much a presence as a medium.

‘I was playing at Oxford. Except for the first few rows where the dons and their wives were sitting, the audience consisted entirely of young people. And they were so keen, so attentive; you cannot imagine. I had thought that in England, as in some other countries, the new generation had no interest in music. But no. I could feel that they were interested as soon as I began. And I must tell you, it was not at all an easy programme. To tell the truth, I had been a little nervous. But when that feeling came to me, the feeling that they were vitally interested after all, I was very, very happy.’

Menotti - A New Medium for Opera

Tom Higgins

Composer, librettist and stage director, Gian Carlo Menotti dominated opera in America for a generation. Tom Higgins examines his life and remembers a personal encounter.

While still a teenager, Menotti crossed the Atlantic to study in America and fell in love with the place. He found it exciting and part of the excitement was the knowledge that all the great composers were there. The Roaring Twenties or the Jazz Age – whatever you call those years – attracted Europe’s foremost artists to the New World. They were escaping the turmoil that threatened the Old. Aged 17 in 1928, Menotti was not yet famous. His celebrity lay in the future, but first he had to be a student at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia – he was there at the suggestion of his fellow Italian, the conductor Arturo Toscanini.

Graduating from Curtis in early 1933, Menotti travelled back across the Atlantic and embarked on an exploration of his native Europe. In Austria he met an aging Czechoslovakian noblewoman, an encounter which inspired him to commence work on his first mature opera, Amelia goes to the Ball. By now Menotti’s fellow student, Samuel Barber, was his partner in life – a relationship that lasted for a generation.