Current Issue

Previous Issues

Spring 2025. Issue 1541

Winter 2024. 1540

Autumn 2024. 1539

Summer 2024. 1539

Spring 2024. 1538

Winter 2023. 1537

Autumn 2023. 1536

Summer 2023. 1535.

Spring 2023. 1534.

Winter 2022. 1533.

Autumn 2022. 1532.

Summer 2022. 531.

Following the dispicable and illegal invasion of Ukraine, the Summer 2022 edition of Musical Opinion carries a large article about Sergei Prokofiev, arguably its most famous composer along with an overview of the Ukrainian classical music scene over the last one...

Spring 2022. 1530.

Winter 2021. 1529.

Autumn 2021. 1528.

Summer 2021. 1527.

Spring 2021. 1526.

Winter 2020. 1525.

Autumn 2020. 1524.

Summer 2020. 1523.

Explore By Topic

Summer 2019. 1519.

Nelly Akopian-Tamarina

Ateş Orga

Delicate and ballerinesque, shaped and rigoured by the post-war Soviets from Stalin to Brezhnev, Nelly Akopian-Tamarina these days is very much the ‘lady in black’ of London life. Living in the past, surrounded by her Russian books, scores and memories, never happiest than when at her dimly-lit Steinway – practicing, fingering, analysing, contemplating into the early hours – she cuts an intensely private figure. Courteous to a fault, a precisely groomed star out of some 1940s romance or spy thriller, she doesn’t reveal much, every now and again reclining in a corner of the Goring or, if, rarely for her, there’s a ‘legend’ playing somewhere, modestly slipping into the greenroom to say a few words from the shadows. Here is a Golden Age lady worthy of Howard Hughes’s reclusiveness, without time for loose friendships, small talk or the daily gossip and fashion highs of the music business.

Social media is abhorrent to her, modern technology only a little less so. In the company of dead ‘friends’ – Beethoven, Chopin, Schumann, Brahms – multiple editions and photocopies of autographs on her ‘pi-ya-no’, a different being is to be found. Logical, demanding, deductive. I’ve never met a mind so keenly sharpened, a perfectionist so refusing to give up.

André Previn - A Personal Reminiscence

Monica McCabe

And so André Previn has passed away…..As it happens, he looms quite large in my life, much more so, I know, than the reverse. In 1968 the music world in Britain was astounded to learn that the well-known Hollywood composer and four times Oscar winner, and jazz pianist, had been appointed Principal Conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra, a post he held until 1979. I meanwhile, just the day before, had been taken on to work for the now-defunct magazine Records and Recording. I assumed that my position would be that of a lowly ‘gofer’. Imagine my astonishment and consternation when my first assignment was to join the queue of some 300 journalists snaking through the corridors of, as I recall, the Savoy Hotel in London, waiting to interview the new maestro. When my turn came I was so nervous I could not even take notes, and wrote up my interview entirely from memory. There were portable recorders at the time, but anyway I did not have one. Previn must have noticed my amateurish nervousness, but he was kindness and patience itself, something I have never forgotten. In retrospect, he might even have preferred my awe to the obvious bumptiousness of some of the tabloid Press.

By 1971 my late husband John McCabe and I had started a relationship which was to last for more than 40 years. John at that time had scored a major success with his song-cycle for soprano and orchestra, Notturni ed Alba, premiered in 1970 at the Hereford Three Choirs Festival.

Bergliot – Two musical settings of a tale of treachery and murder in mediaeval Norway

Beryl Foster

The renowned authority on the great Norwegian composer Grieg explains the background to his melodramatic setting of Bjørnson’s text, alongside that of Grieg’s Danish contemporary, the Danish composer Peter Heise, for whom the text was originally written.

In 1871 Edvard Grieg produced one of his most unusual and least known works, in a genre rarely heard today, that of a recitation over an instrumental accompaniment: the melodrama Bergliot. The author was Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832-1910), whom Grieg first met in Denmark in the summer of 1865. They were to become good friends and Grieg set a number of Bjørnson’s occasional pieces and also four songs, published as op.21.

The text of Bergliot is based on a scene from the saga of Harald Hårdråde[i] from the Heimskringla, the history of the Norwegian kings by Snorre Sturlason

Hastings Renaissance

Dr Brian Hick considers the rebirth of a musical heritage on the South Coast.

Anybody who thinks of Hastings as a musical backwater has obviously not been down to the South coast recently. Since Brazilian musician Marcio da Silva took over Hastings Philharmonic there has been a quiet revolution both in the quality and the scope of what is on offer. When I first moved to Hastings in the 1980s there were still visiting professional orchestras at the White Rock Theatre but nothing of a similar standard locally. Since then the touring concerts have dried up and for many years we had to travel to Eastbourne, Brighton or Tunbridge Wells to find any orchestral events within a reasonable distance. The choral tradition had always been strong in Hastings but the Philharmonic Choir only gave a couple of concerts a year and its traditional Christmas Celebration.

All that changed when Marcio arrived in 2012 and the number of concerts began to expand exponentially. In 2016 the new Hastings Philharmonic Orchestra, an entirely professional body of young musicians, was formed and, as a result, last year brought us thirteen events, ranging from a Tango evening to the Verdi Requiem, via chamber concerts and an Opera Gala.

Musical Illusions in Films

Imogen Windsor

Music can contribute hugely to a film artistically: to the drama, the romance, the joy or despair. So when an actor is playing the role of a performing musician, how can they prepare properly for the job?

Film soundtracks are big business. Music adds a vital dimension to the world of cinema and has the power to trigger instant nostalgia for a favourite film. Film composers are recognised for their huge contribution to the end product, and to the industry as a whole. Soundtracks can generate substantial revenues in themselves: the best-selling soundtrack of all time is from 1992 film The Bodyguard, achieving an impressive 18 million certified sales.

Music in films can serve various purposes – as an audio backdrop or landscape; to aid story progression or pacing; or to convey a mood or concept. Composers often create themes for particular characters, events, locations and ideas, and a film’s signature song can even become more famous than the film itself. But sometimes the music is totally integral to the film, and the sight of a particular actor playing an instrument is an important part of the plot.

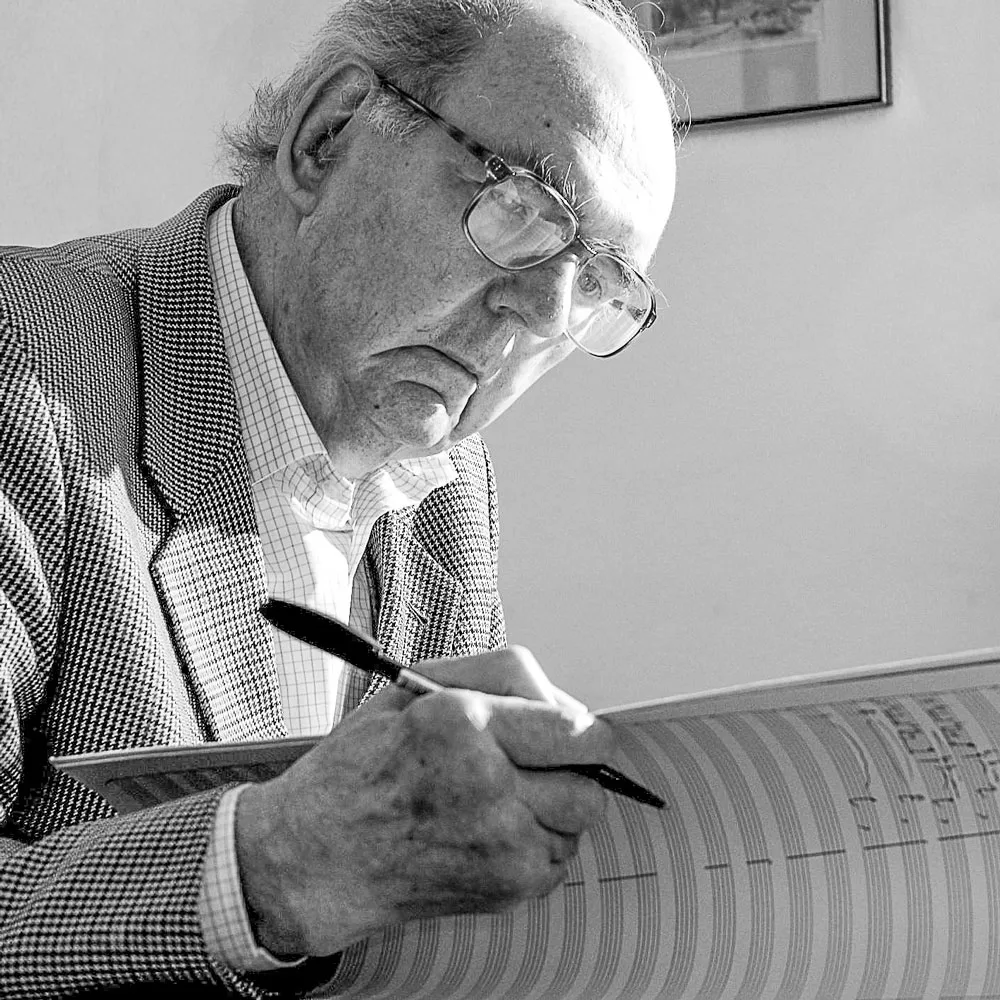

A tribute to John Joubert

Christopher Morley

It is a comfort to all who loved him — not just family and friends, but all of those who had been touched by the warmth of his compositions — that John Joubert, who passed away on January 7 at the age of 91 after a fall on New Year’s Day had lived long enough to witness a well-deserved resurgence of interest in his music.

Inscrutable mandarins in the musical establishment had long banished his work, dismissing its communicativeness, its sincerity of expression, its acute response to text, its rhythmic precision, and so many other qualities the music-loving public listens out for, as outmoded.

Yet the mild-mannered (but quietly sardonic in friendly company) composer continued to create works in every genre, approaching 200 opus numbers, chiefly to commission; though his masterpiece, the opera Jane Eyre, was a genuine labour of love, cooking on the back-burner for so many years while he attended to those necessary commissions. It was probably the highlight of Joubert’s professional life when the opera was premiered at the splendid Ruddock Hall of King Edward’s School, Edgbaston in October 2016 to immense acclaim, with the recording subsequently released on the SOMM label, whose previous issues had done so much to further the rehabilitation of this beloved composer.

Wittener Tage für Neue Kammermusik (Witten New Chamber Music Days)

Claire McGinn

In its 50th installment, the Witten New Chamber Music Days festival 2018 featured a suitably superlative array of new works. Spread across the scenic venues of the Saalbau concert hall, the Art Museum, and the Rudolph Steiner School in Witten, North Rhine-Westphalia, the positive audience energy, scintillating range of artworks, and impressive style and skill of the performers were apt for a celebratory series of events.

Composer-singer Agata Zubel premiered her 2018 cycle of Cleopatra’s Songs, setting a psychological rollercoaster of vituperative verse condensed from Shakespeare’s play. From the guttural opening command ‘Give me some music; music, moody food’, through bitter, burning melismatic fury; wild registral leaps; and the almost painfully drawn-out entreaty ‘Think you there was, or might be, such another man as this I dream’d of?’, the contrasting shades of Zubel’s diverse vocal palette complimented her high-voltage stage presence.

My New Music

Matthew Taylor

Since this series on contemporary British symphonies began (having previously taken in the Eighth Symphony of David Matthews (April 2015) and the Fifth Symphony of John Pickard (April 2016)), the frequently bleak outlook for this genre has been redressed through the 21st Century Symphony Project. Inaugurated by Kenneth Woods on becoming Artistic Director of the English Symphony Orchestra in October 2016, its aim is to commission nine symphonies by nine composers. The first of these was the Third Symphony by Philip Sawyers, premiered in London on 28th February 2017, followed by the Ninth Symphony of David Matthews in Bristol on 9th May last year. Now comes the turn of Matthew Taylor, whose Fifth Symphony is to receive its first hearing from Woods and the ESO at Cadogan Hall on Sunday 9th June.

Symphonic writing has been a mainstay of Taylor’s output from the outset. Finished in 1985, his First Symphony certainly lives up to its Sinfonia Brevis subtitle – the single movement unfolding continuously such that its preludial opening sets up an anticipation only obliquely fulfilled by the ensuing ‘Pesante’; after which, a lithely propelled intermezzo leads into the culminating ‘Animato’ whose accruing momentum is pointedly dispelled in a hushed coda.