Current Issue

Previous Issues

Spring 2025. Issue 1541

Winter 2024. 1540

Autumn 2024. 1539

Summer 2024. 1539

Spring 2024. 1538

Winter 2023. 1537

Autumn 2023. 1536

Summer 2023. 1535.

Spring 2023. 1534.

Winter 2022. 1533.

Autumn 2022. 1532.

Spring 2022. 1530.

Winter 2021. 1529.

Autumn 2021. 1528.

Summer 2021. 1527.

Spring 2021. 1526.

Winter 2020. 1525.

Autumn 2020. 1524.

Summer 2020. 1523.

Spring 2020. 1522.

Explore By Topic

Summer 2022. 531.

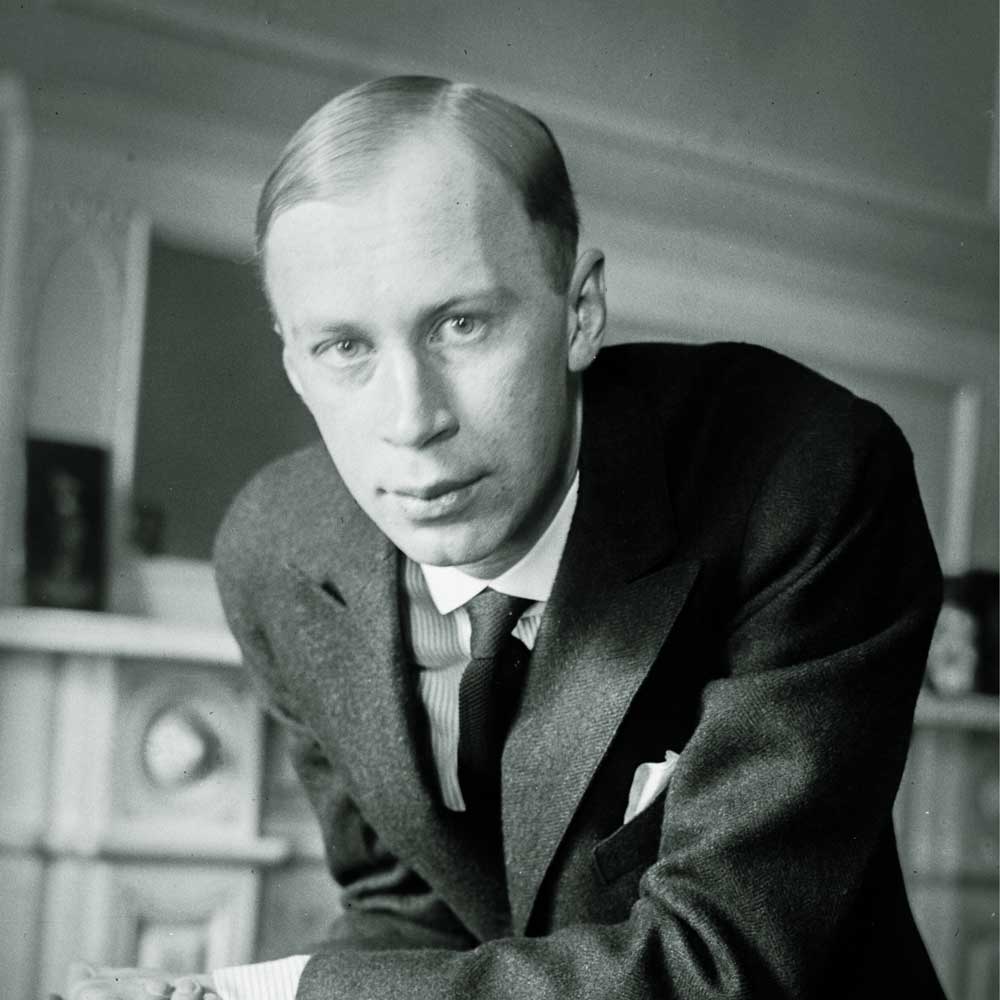

Aspects of the piano music of Sergei Prokofiev – Ukraine’s Greatest Composer – with a note on his Opus 75

Robert Matthew-Walker

As a measure of support to the people of Ukraine in the wake of the invasion of their country in February, the Editor comments on one of the less-appreciated features of the country’s greatest composer.

Although it would not be entirely accurate to claim Sergei Prokofiev to have been a child prodigy, as a boy his superlative musical gifts were such that by the age of nine he had completed the piano score of an opera, The Giant. When he was just 13 years old, he was admitted to the St Petersburg Conservatoire after having composed a second opera as well as other works. At the Conservatoire, his teachers included Anna Essipova for piano and Rimsky-Korsakov and Liadov for composition, but Prokofiev had already decided his career was to be in composition, a career that was to continue until the day he died (March 5th 1953) at the age of 61.

Mikhail Matyushin (1861-1934) – a neglected Russian master of genuine art

Gregor Tassie

Matyushin is almost completely forgotten in today’s music world, however his role as a musician, painter, poet, sculptor, musicologist, and teacher blazed an astonishing path in the first decades of the 20th century. He played in the Imperial Court Orchestra for thirty years, met Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Rubinstein, Prokofiev, and Stravinsky and was one of the leading futurists in Russia. The concepts of the Russian futurists were similar to those of Fillippo Tommaso Marinetti’s “Il manifesto del Futurismo” (1909). The Italian poet rejected the quiet, and passive laissez-faire of the Italian Ottocento society and called for the celebration of new technology, speed, and innovation. The strictures of the Russian futurists were not as all-embracing, and indeed when Marinetti visited Russia in 1914, he was ostracized by the Russians, who detested his love of militarism, national-chauvinism, and anti-feminism. The distinguishing features of the Russian futurists were revolt against old values, anarchism, and mass actions, the rejection of traditional art, creation of new art forms, rejection of traditional forms of speech, and use of new speech forms, rhythms, poster art, slogans, and experimentation in new technology.

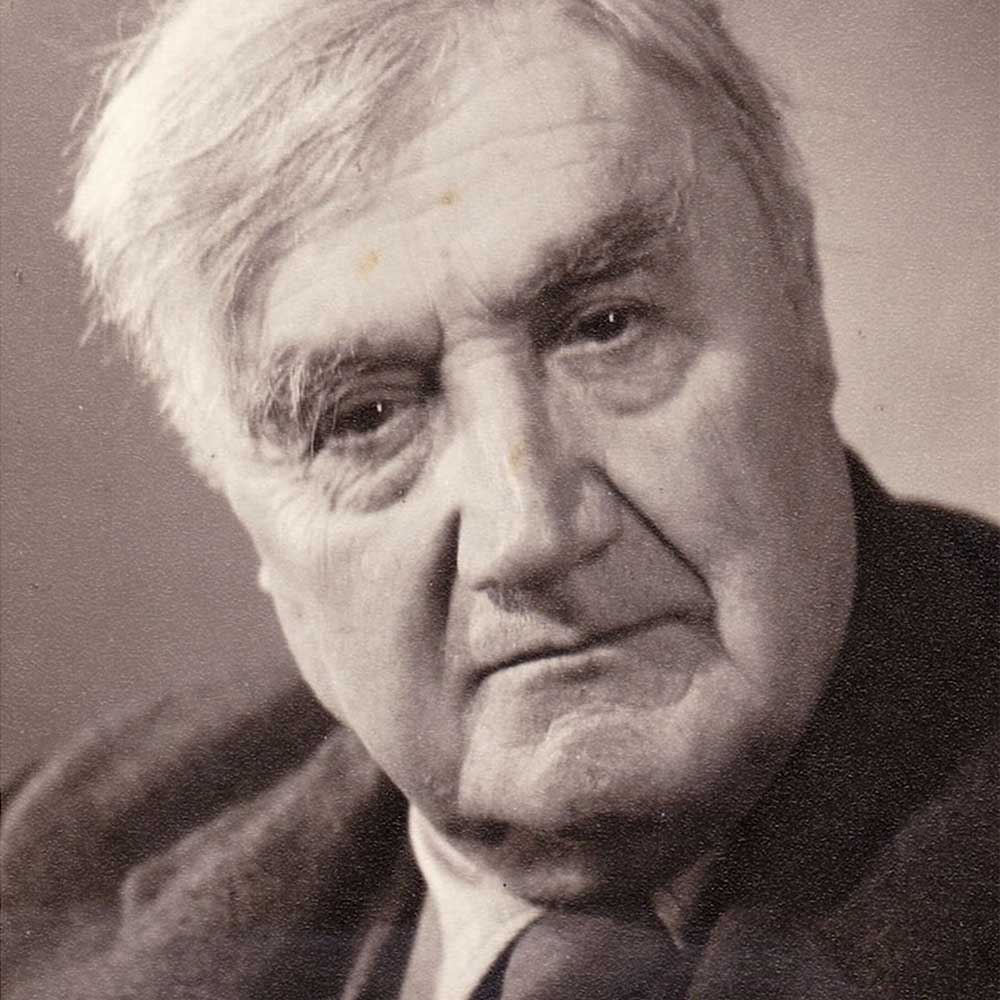

Recording the Vaughan Williams Symphonies

Andrew Keener

In the year of the composer’s sesquicentenary, the international recording producer and musician recalls some experiences in the control rooms

A soft D major horn call over a pedal C on cellos and basses, and I am back in the small music room in Barry Boys’ Comprehensive School. Our A-level music teacher, Dyfrig Thomas, has put Sir Adrian Boult’s 1969 recording of the Fifth Symphony on the turntable, and with Samuel Palmer’s painting The Magic Apple Tree depicting sheep safely grazing within a rich orange landscape looking up at me from the LP sleeve, I have begun a journey which enchants me to this day.

The Fifth Symphony also marked the beginning of my journey in the recording studio with these life-changing works. I thought I knew the piece, and I suppose I did (my worn LP of Boult’s recording bears witness to its hundreds of playings). But here I was in Liverpool in September 1986 with Vernon Handley revealing to me the orchestration, structure and meaning of the piece in a way I had only begun to imagine. What better studio baptism for a young recording producer who, had he but known it, would over the next three decades go on to embark on complete cycles with four conductors as well as several other individual recordings?

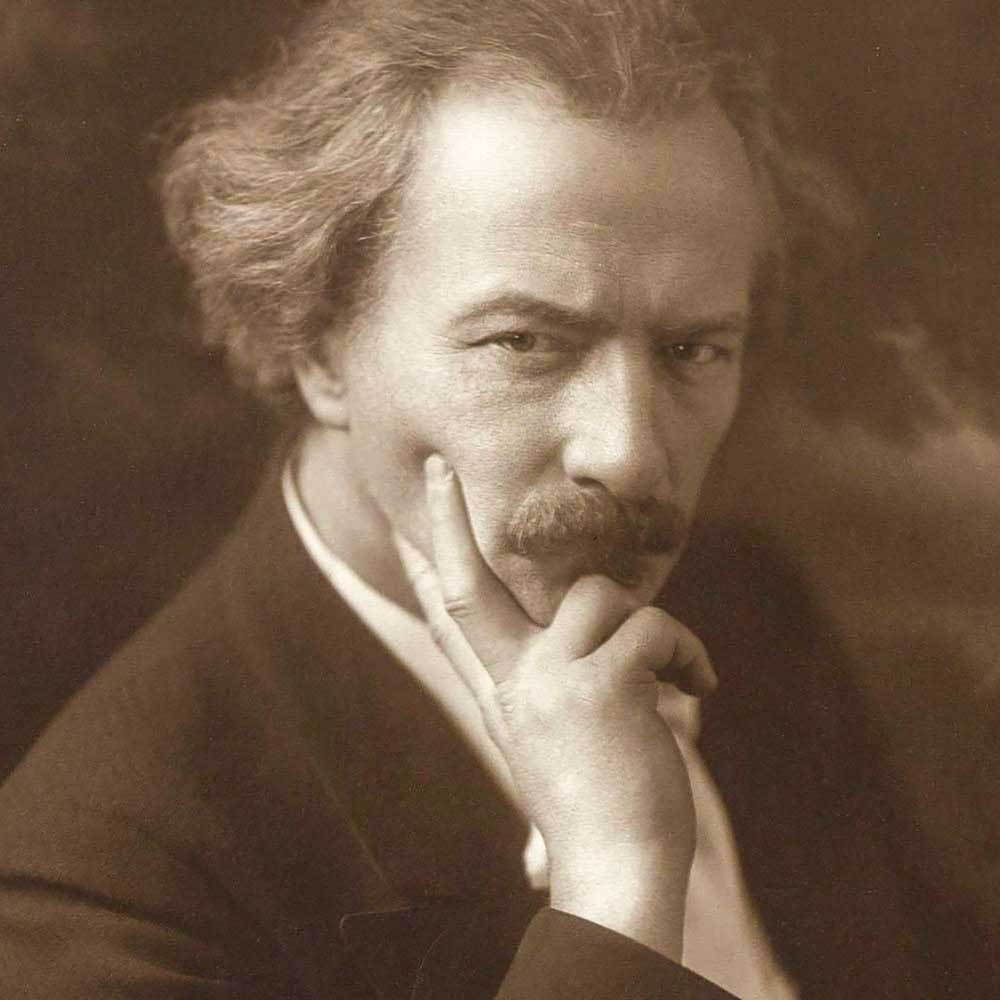

Ignacy Paderewski (1860-1941): virtuoso of Polish independence

George Byczynski

Aside from being an exceptionally talented musician, Ignacy Jan Paderewski is considered a freedom fighter and one of the fathers of Polish regained independence after the Great War. How has a pianist helped his country reappear on the European map and eventually become Poland’s Prime Minister?

Ignacy Paderewski was born on the 6th of November 1860 in Kuryłówka in Podolia. His hometown makes a prime example of the volatility of the borders in Central and Eastern Europe. The region used to be Polish, until Poland was partitioned for 123-years by Prussia, Austria, and Russia. Paderewski’s childhood was marked by the brutality of the Russian occupation, as well as the efforts of his relatives in the struggle for Polish independence. Despite being born into a country that did not exist on the map, his loyalties were clear. He cultivated two great passions throughout his youth: playing the piano and the dream of an independent Poland.