Previous Issues

Autumn 2024. 1539

Summer 2024. 1539

Spring 2024. 1538

Winter 2023. 1537

Autumn 2023. 1536

Summer 2023. 1535.

Spring 2023. 1534.

Winter 2022. 1533.

Autumn 2022. 1532.

Summer 2022. 531.

Following the dispicable and illegal invasion of Ukraine, the Summer 2022 edition of Musical Opinion carries a large article about Sergei Prokofiev, arguably its most famous composer along with an overview of the Ukrainian classical music scene over the last one...

Spring 2022. 1530.

Winter 2021. 1529.

Autumn 2021. 1528.

Summer 2021. 1527.

Spring 2021. 1526.

Winter 2020. 1525.

Autumn 2020. 1524.

Summer 2020. 1523.

Spring 2020. 1522.

Explore By Topic

Summer 2025. Issue 1542

Meeting Shostakovitch

Robert Matthew-Walker

In 1972 I was head of the classical department of CBS Records UK. At that time there was a trade newspaper, Music Week, which had a regular one-page section devoted to classical music. The Editor and main contributor to that page was Evan Senior, a well-respected classical music journalist who had been the founding editor of Music and Musicians in 1950. I never knew quite how old Evan was, but he was certainly in his mid- to late-seventies – if not older – at that time.

I would speak with Evan often, and have lunch with him to keep him up to date with CBS’s activities. One day in July he called me to ask ‘Would you like to meet Shostakovich?’ Of course, my answer was ‘Yes, very much so’, and he explained that Shostakovich was coming to England for a couple of days, en route to Dublin where he was to receive an honorary Doctorate from the city’s University.

He was apparently to stay overnight in Cambridge, but I am unsure if at that time he was to meet the Fitzwilliam String Quartet who went on to record all of his fifteen String Quartets for Decca, and the University had arranged for a small press reception to meet him.

Evan however did not relish the idea of driving all the way from north London to Cambridge and back in one day at his age – he was a little uncertain behind the wheel – and asked me if I would drive him, meet Shostakovich and return by the mid-evening.

I needed no second bidding, of course. So we went – I think it was to Fitzwilliam College, but I cannot now be certain. I know he and his young wife went to King’s College, seeing the great Chapel, where they were met by David Willcocks. Anyway, Evan and I were shown into a room with about twenty or so people, and there was the great man, smaller than I imagined, with a young lady of about the same height – who I later learned was his third wife – alongside a big butch KGB minder, and a lady (I assumed Russian) who appeared to be in charge of Shostakovich’s party.

Photo: Deutsche Fotothek

Sir Charles Mackerras 1925-2010 - a centenary tribute

Tom Higgins

‘Ah, good to see young Mackerras here,’ said Sir Adrian Boult at the Royal Albert Hall. Boult, then in his mid-eighties, and the ‘young Mackerras’ were sharing a BBC Promenade concert. They were also sharing the conductor’s dressing room, allowing Mackerras to overhear Boult’s courtly aside. Captivated, Mackerras never forgot it and thereafter seldom missed a chance to tell the story, evoking its irony by adding with his famous grin, ‘At the time I was over 50!’

They had first met almost 30 years before, when Mackerras, newly arrived from Australia, sought Boult’s advice on how to make a career in Britain. He found Boult helpful and generous with his time. Soon he gained a job with Sadler’s Wells Opera, joining the company in 1947. An opera house needs a wide range of talents and Mackerras possessed several. He was appointed to fill two jobs: second oboe in the orchestra and repetiteur. A hint of the future came with some backstage conducting.

It was a good start, but Mackerras’s instinct was to acquire more training. The chance came less than a year after arriving in London. He won a British Council Scholarship to study conducting with Vaclav Talich in Czechoslovakia. Soon he exchanged London for Prague, but not before his marriage to Judith Wilkins, principal clarinet in the orchestra. She went with him.

Czechoslovakia charmed him. He learned the language, but more significantly, he discovered the operas of Leoš Janáček.

Three Who Quit: Ives, Elgar, Sibelius and the Crisis of Modernism

Joseph Horowitz

In November 1926, Charles Ives descended from the upstairs studio of his ample West Seventy-fourth Street apartment with tears streaming down his face. “I can’t seem to compose any more,” he told his wife Harmony. “I try and try and nothing comes out right.” He was fifty-two years old and would live another twenty-eight years, creatively spent.

This well-known anecdote feeds the imagery of Ives the picturesque eccentric: a serendipitous modernist anomaly, a stranger to his own time and place who idiosyncratically and haphazardly forecast post-World War I notions of originality. And yet many composers, both in Europe and the United States, experienced a comparable crisis. The best-known cases were Edward Elgar and Jean Sibelius. Like Ives, they were Romantic symphonists in the Germanic tradition. Like Ives, they virtually stopped composing in the 1920s. Like Ives, they were strangers to modernism and – to a significant extent – to modernity. And there is a third similarity, a rooted relationship to Nature that was both elemental and national. What New England was for Ives, the Malvern Hills and the Finnish forests were to Elgar and Sibelius.

Born in 1874, Ives remains too often framed as a ragged cultural footnote. He more deserves to be remembered as the supreme American concert composer, a musical genius, an iconic self-made American to set beside Emerson, Melville, and Whitman. His stage, his status, were and are international.

Within a decade of Charles Ives’ death in 1954, contemporary composers of tonal music could not be taken seriously.

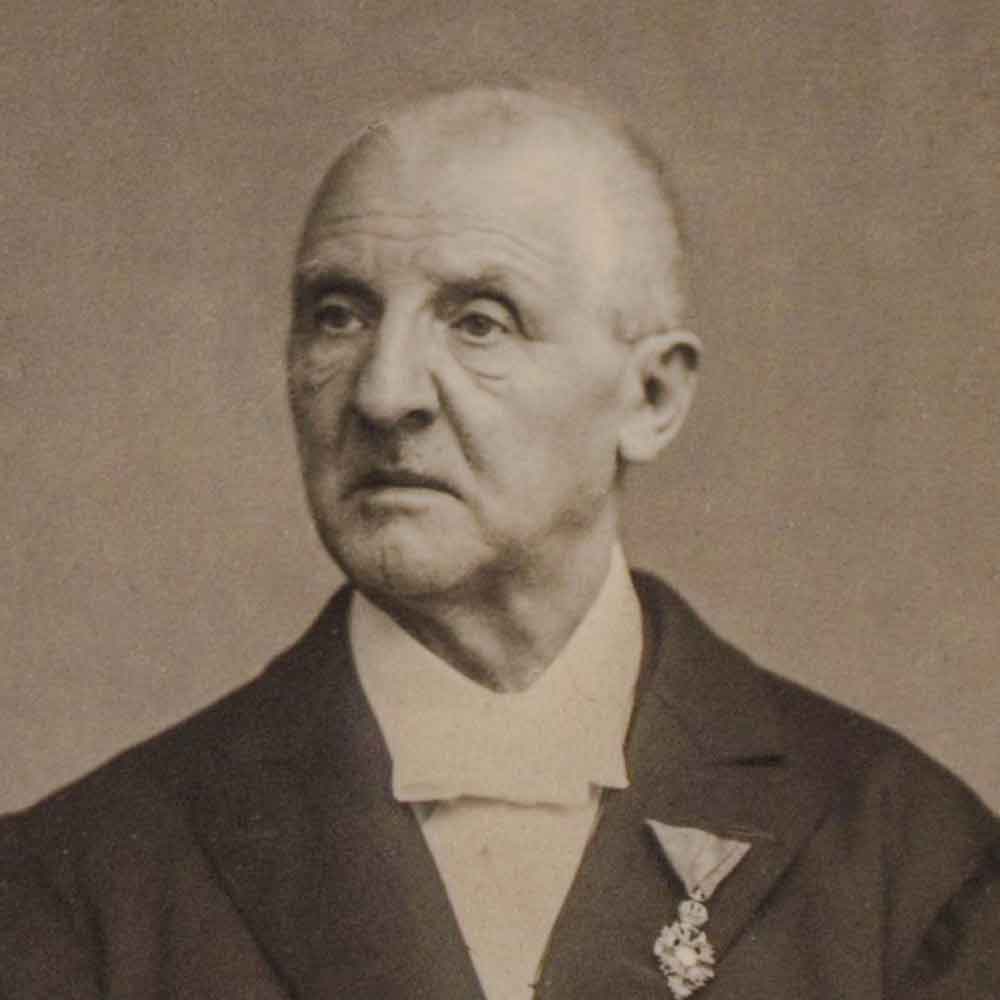

Glimpses of Astra - What would Bruckner’s unwritten opera have been like?

Dr Martin Pulbrook

Hans-Hubert Schönzeler, in a 1970 book, has given us a tantalising glimpse of Bruckner’s unrealised plans for Astra [in Bruckner, published by Calder and Boyars London, p.99]: ‘During [his] last years Bruckner also toyed with the idea of composing an opera to a libretto by Gertrud Bollé-Hellmund with the title Astra. The subject had been selected from a novel, Die Toteninsel by Richard Voss, and was, as Bruckner had demanded, ‘à la Lohengrin, romantic, full of the mystery of religion, and completely free from all that which is impure.’ There, however, the matter rested. Bruckner never made as much as a preliminary sketch, and it remains an interested matter for conjecture what an opera by Bruckner might have sounded like.’

There is, I feel, something off-key and inappropriate in Schönzeler’s dismissiveness here – the implication being, clearly, ‘an opera by Bruckner couldn’t have been any good, so we may not in fact be missing very much.’ I think the implication is wholly wide of the mark and undeserved, and I wish here to try to approach and evaluate the question of Astra from a more sympathetic point of view. For it seems possible and likely to me, pace Schönzeler, that Bruckner’s death in October 1896 has robbed us of what would have been a masterpiece of its kind.