Current Issue

Previous Issues

Spring 2025. Issue 1541

Winter 2024. 1540

Autumn 2024. 1539

Summer 2024. 1539

Spring 2024. 1538

Winter 2023. 1537

Autumn 2023. 1536

Summer 2023. 1535.

Spring 2023. 1534.

Winter 2022. 1533.

Autumn 2022. 1532.

Summer 2022. 531.

Following the dispicable and illegal invasion of Ukraine, the Summer 2022 edition of Musical Opinion carries a large article about Sergei Prokofiev, arguably its most famous composer along with an overview of the Ukrainian classical music scene over the last one...

Spring 2022. 1530.

Winter 2021. 1529.

Autumn 2021. 1528.

Summer 2021. 1527.

Spring 2021. 1526.

Autumn 2020. 1524.

Summer 2020. 1523.

Spring 2020. 1522.

Explore By Topic

Winter 2020. 1525.

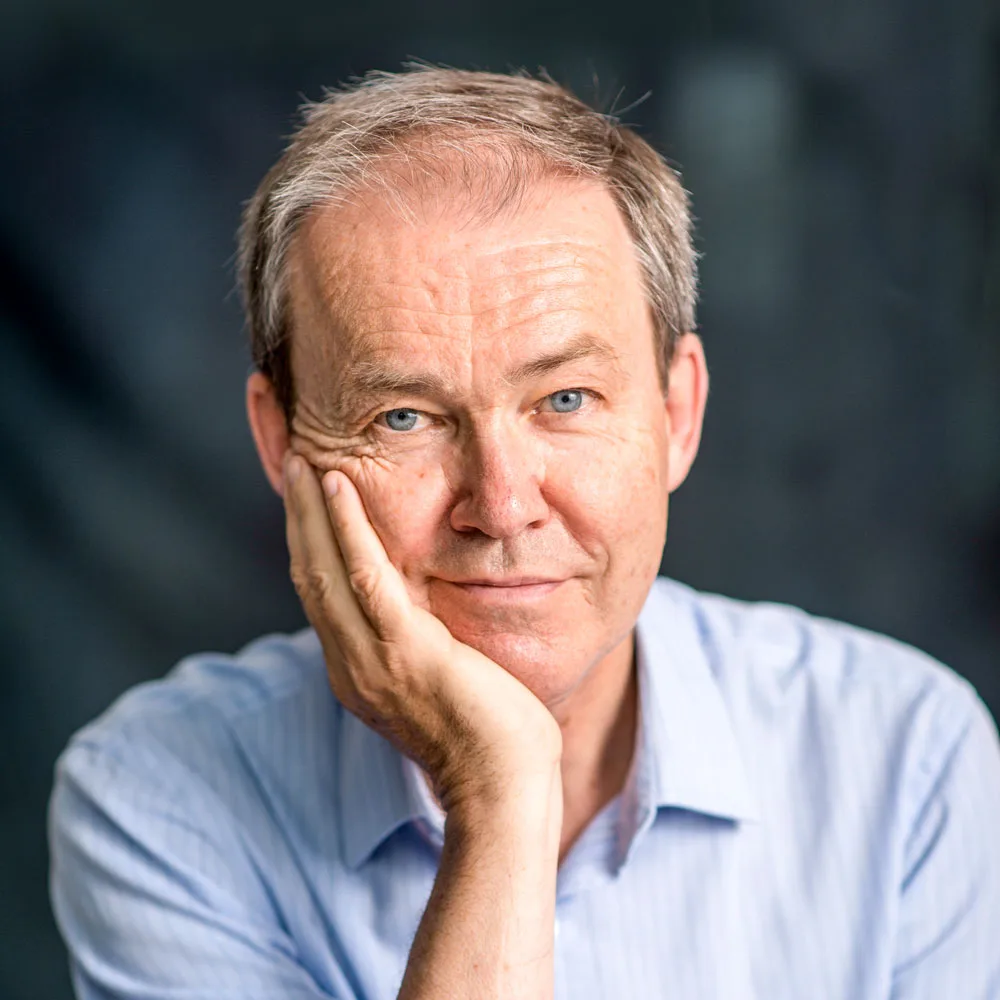

Edward Gregson at 75

A birthday tribute by producer and writer Paul Hindmarsh

Edward Gregson celebrated his 75th birthday on 23 July. Born in Sunderland six weeks after VE day, he has reached that time of life when most of us would be thinking of taking up some relaxing pastimes – tending the garden, walking the dogs, playing a favourite piece of Brahms or Beethoven on the piano or simply enjoying a glass of fine red wine in the garden while listening to the swifts ducking and diving overhead. Eddie (as he is widely known by his many friends and colleagues) achieves all that and much more. Retirement is not a word he or probably any high-achieving creative artist would recognise. Gregson at 75 is enjoying something of a golden period of productivity, which is not at all surprising, since he now has the time to devote solely to his music.

For over 30 years Gregson’s professional life followed parallel paths, one towards the top tier of music education and the other towards the international reputation he now enjoys as a composer. In 1976 he was appointed to the music staff of Goldsmith’s College, London. Twenty years later, Professor Gregson, as he had become, moved to Manchester to become only the second Principal of the Royal Northern College of Music, following the retirement of John Manduell. Nurturing the skills of future generations of composers, teachers, and performers brought him deep satisfaction.

‘BILLY’

Tom Higgins

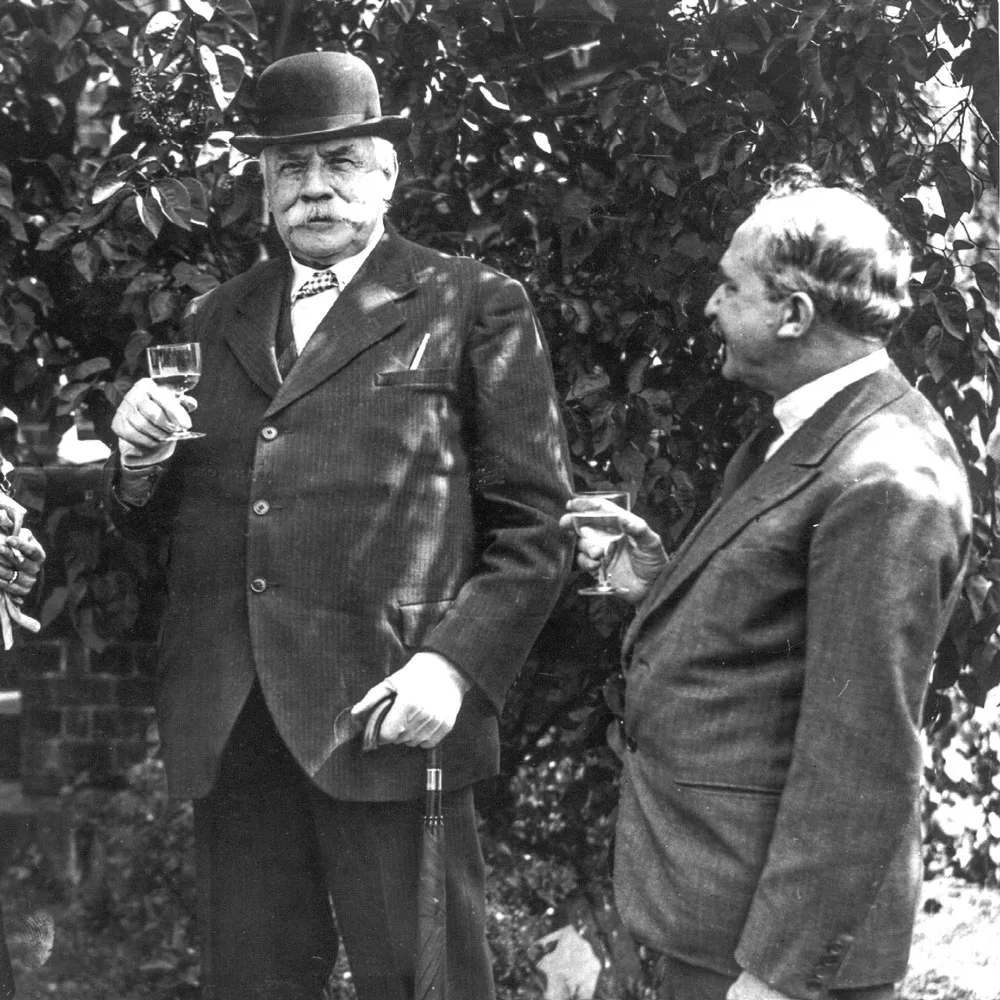

Tom Higgins examines the friendship between Sir Edward Elgar and W H.(Billy) Reed.

Caractacus was the first piece of Elgar’s music that W.H. Reed played under the composer’s direction. Nearly 36 years later it was to be the last. In between lay an extraordinary friendship of close understanding.

Like Elgar, William Henry Reed came from the west of England – he was born on 29 July 1875 in Frome, Somerset. He studied violin and composition at the Royal Academy of Music, and soon entered into the ranks of London orchestras, joining Henry Wood’s Queen’s Hall Orchestra at an early stage. In 1904 when members of this orchestra broke away from Wood and formed the London Symphony Orchestra, Reed was among the rebels. In 1912, he became the LSO’s leader and held that position for over 20 years until 1935.

When not busy as an orchestral player, Reed composed a considerable body of music. Posterity has not judged his output to be of any great significance.

A Journey of Becoming

Philip Sawyers

Philip Sawyers talks to Richard Whitehouse about his unexpected but successful transition from performer to composer.

The emergence of Philip Sawyers as a major symphonist of his generation has been among the more significant aspects of latter-day British music. Unexpected, too, given he had largely abandoned composition in his early twenties to focus on his career as second violinist in the Orchestra of the Royal Opera; supplemented by coaching for Kent County Youth Orchestra alongside peripatetic teaching at various schools and colleges. Speaking recently, the South London-born Sawyers is wont to express continuing surprise that a life centred on music was possible in the first instance. ‘‘There was little in my earlier life to indicate the importance music was to have. Had I not, quite by chance, heard Mozart’s overture to The Marriage of Figaro then come across a violin that the family of a friend of my older brother was throwing out and started lessons when I was 13, my future might have turned out very differently’’.

Not that being a late starter was a deterrent, Sawyers passing his Grade Eight with distinction just five years later then studying at Dartington College of Arts in Totnes. There he received violin tuition with Colin Sauer and composition lessons from Helen Glatz, a one-time pupil of Vaughan Williams whom Sawyers recollects with a mixture of admiration and affection. ‘‘Helen was a remarkable woman and a notable composer who has not had anything like her due. She certainly gave me greater confidence in my ability to compose, even if that has proven to be a longer-term objective than I could then have imagined’’.

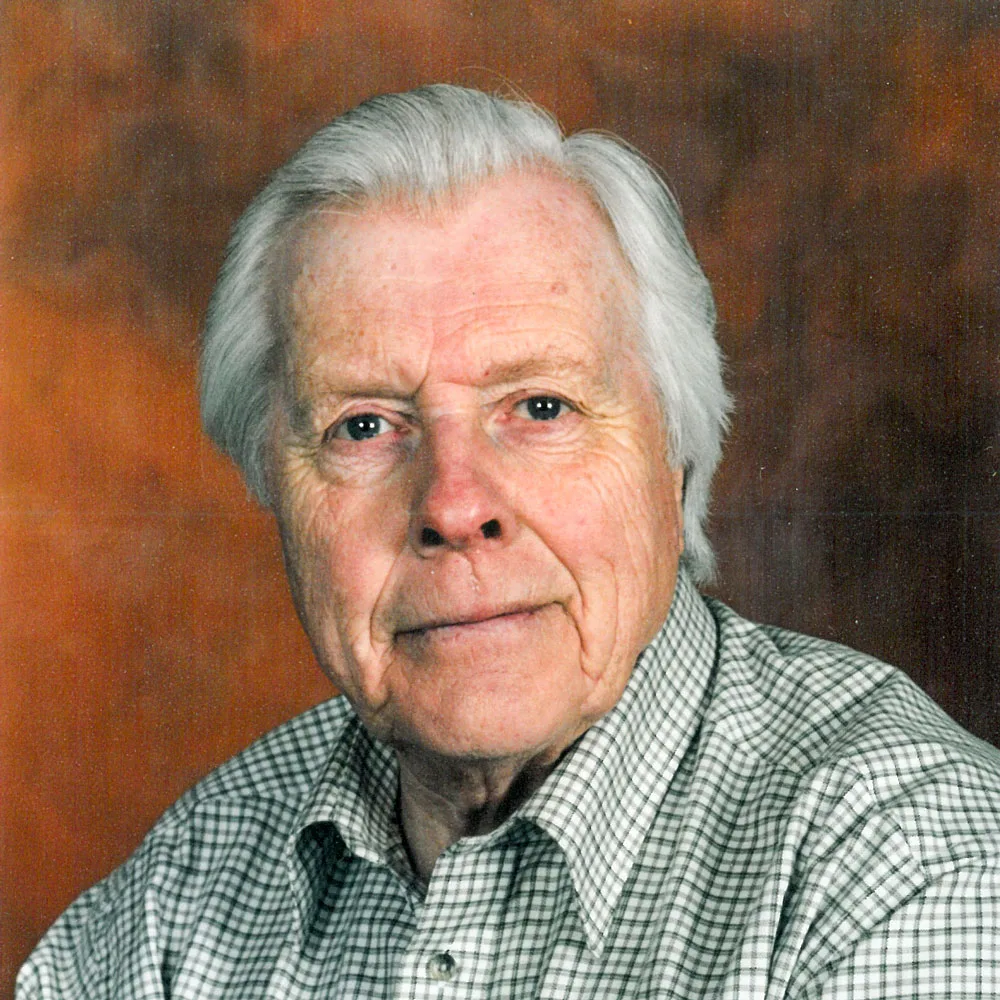

Sir John Manduell

John Turner

Marking the recent Prima Facie recording of music by Sir John Manduell, Founding Principal of the Royal Northern College of Music, John Turner offers this personal tribute to a close friend and colleaague.

I first met John when he asked me to teach a recorder student at the Royal Northern College of Music, at three pounds fifty an hour! How times (and teaching rates), have changed! We subsequently realised that John’s sister Gillian, in New Zealand, was married to the clergyman brother of one of my colleagues in the law firm in which I was a partner. John was always punctilious in mentioning this coincidence, to avoid any possible charge of nepotism. Another connection arose through a university friend of mine who taught geography at Giggleswick School, and tutored both his sons Jonathan and Julius there.

John’s first piece for me, for solo recorder, arose out of a mutual connection with the composer William Alwyn, who was John’s greatly admired first composition tutor at the Royal Academy of Music.

Recording the complete piano works of Beethoven, and Tippett’s piano concerto with the composer

Malcolm Miller

Martino Tirimo in conversation with Malcolm Miller, part two.

We discussed whether having recorded a work, Tirimo feels he would play it differently, change his interpretation. As he responded, “ Nothing is fixed… allow me to mention one example I am very fond of mentioning this since it was an eye opener for me. You may know that I had a … I still think that the Tippett piano concerto is one of the great piano concertos of the twentieth century and should be played much, much more. I had the

great fortune to do a number of concertswith Sir Michael and we recorded it as well. I was extremely nervous when I first went to play it to him, because I thought that his metronome mark for the first movement was just too fast. And I didn’t know quite how to approach this. So, we had a wonderful lunch and a wonderful conversation for a couple of hours, and then it was time for me to play and I said ‘Sir Michael I have to before I play I have to apologise to you I just don’t feel this opening movement at this tempo…that you ask.’ ‘Well, play and we will see’ he said. And when I finished, to my great relief he said ‘But that’s exactly how I want it’. I was so overjoyed .